Here are some excerpts from Ed Fallon’s book, Marcher, Walker, Pilgrim.

From the Introduction

Sean Glenn and Mack Wilkins

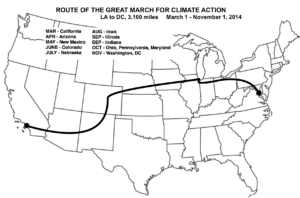

Walking across America is an enormous challenge. Pounding pavement, gravel, and sand 15 – 20 miles a day for eight months is unkind to one’s body, even under the best conditions. The difficulties are markedly greater when one walks on a schedule, as we did, with rallies and events planned along the route weeks and even months in advance.

When you walk on a schedule you can’t take time off for an illness. You can’t rest for a week to recover from an injury. You can’t take a leave of absence for a funeral or a wedding. You simply keep going or you quit.

It became important for me to try to walk every step of the way. Sure, there’s something gratifying about traversing the breadth of a continent on foot. But far more important, I saw the March as a moving dramatization of the urgency of the climate crisis. Our steps were sacrificial performance art, showcasing the deep individual commitment we all must make to assure our collective survival in the New Climate Era.

It became important for me to try to walk every step of the way. Sure, there’s something gratifying about traversing the breadth of a continent on foot. But far more important, I saw the March as a moving dramatization of the urgency of the climate crisis. Our steps were sacrificial performance art, showcasing the deep individual commitment we all must make to assure our collective survival in the New Climate Era.

From Chapter 1: Failure

I lie still, like a wounded animal hoping to avoid detection from a real or imagined predator. I try to stay warm yet feel unable to move. The reality of my isolation presses ever harder against my chest, against my heart.

I lie still, like a wounded animal hoping to avoid detection from a real or imagined predator. I try to stay warm yet feel unable to move. The reality of my isolation presses ever harder against my chest, against my heart.

I had left the other marchers a week ago after conflicts that had grown so virulent and tiresome that I desperately needed a break. I needed to walk in peace before rejoining the group for our final hike to the White House. But now I miss the camp, despite its dysfunction. I miss the familiar comfort of my tent. I half-hope, half-imagine, that Sarah Spain, the March’s gregarious logistics director, will drive by, sense my presence, and pull over to rescue me.

Sarah has certainly worked her share of miracles on the March, instantly connecting with whoever stood between us and whatever we needed. In an Arizona bar, Sarah’s cowboy hat and eagerness to pose for a photo with a shotgun scored us a rodeo-ground campsite. In New Mexico, her charm with a commune of aging hippies landed us foot massages and a delicious meal.

Whether it was campsites, food, vehicle repair, or showers, Sarah always found a way to deliver.

But today, there would be no Sarah-magic.

From Chapter 4: Post-Victorian Man

Despite occasional spells of doubt, I nurture the notion that as a man slogs through the tasks and tumult of his daily life, he eventually meets the woman of his dreams and they both know with unshakable conifdence that they’re meant to spend the rest of their lives together. Admittedly, I’ve met only a few such couples in the flesh, though they can be found in abundance in fictional literature, the bulk of it pre-dating the 1950s.

For better or worse, somewhere in the middle of the last century, there occurred a seismic shift in how American males regarded romantic relationships. The love-intoxicated, idealistic man-hero of Victorian times sobered up. He accepted the fact that divine forces weren’t simply going to guide him to his true love, where recognition of their predestined union would be mutual and instantaneous.

Post-Victorian Man — P-V Man, we’ll call him — learned that love is more than chemistry and predetermination. With the strength of character and clarity of purpose that have come to defne our gender over the millennia, P-V Man knew that if he were to reel in an adequate life partner it would, alas, require time and effort. He wisely pivoted his strategy, seized the initiative, and began to spend prodigious amounts of time in bars.

By virtue of either my Catholic upbringing, idealistic nature, or perhaps a genetic defect, I totally missed the P-V chapter of American-male history. Through five decades and two divorces, my unfettered confidence in the reality of the Victorian love model remains rock solid.

Mostly.

From Chapter 6: In the Shadow of Valero

The March begins. A group of students wearing dust masks and dragging a replica of a polar bear leads us into the street. I sense a collective rush of ecstasy among marchers as the first steps of this incredible 3,000-mile journey begin. I look at Sean Glenn, an amazing young woman who has decided to march the entire distance in silence. Sean is beaming. I beam back. Sean spent the weeks leading up to the March in Des Moines and, as we trained together, she’d become like a daughter to me.

The March begins. A group of students wearing dust masks and dragging a replica of a polar bear leads us into the street. I sense a collective rush of ecstasy among marchers as the first steps of this incredible 3,000-mile journey begin. I look at Sean Glenn, an amazing young woman who has decided to march the entire distance in silence. Sean is beaming. I beam back. Sean spent the weeks leading up to the March in Des Moines and, as we trained together, she’d become like a daughter to me.

We walk through largely Hispanic neighborhoods, the Pacific Ocean fading behind us and the skyline of Los Angeles opening before us. People line the street to cheer or wave from their homes. It feels more like a parade than a march. The sky had looked foreboding all morning, but so far there’s no rain. “Maybe the clouds blew their wad the past three days,” I say to myself. “Maybe we’ll get through today without a drenching.”

At the two-mile mark, our numbers drop to about 100 stalwarts who intend to go the day’s distance — 19.4 miles through Los Angeles’ industrial underbelly and some of its most impoverished neighborhoods.

About a mile later, the skies open to a flood of cold, driving rain that plagues us the rest of the day. The rain is like a strong summer storm in the Midwest, complete with thunder, lightning, and torrential downpours. The rain turns city streets into raging rivers that push against the curbs and eventually flood the sidewalks. We cross intersections wading through water up to our calves. The current flows so fast some marchers feel like they could be swept away.

Our organized march quickly devolves into a struggle for survival.

From Chapter 14: Hypothermia

Nature and I have always been lovers. As a kid, after my bus ride home from the torture chamber of Catholic grade school, Nature would soothe my wounds. Her love helped me forget, at least for a time, the physical and verbal beatings by bitter, barren nuns too old to teach and too senile to care.

Nature helped me forget the time I was slapped hard in the face for the crime of waving to a friend through the window of the classroom door.

She helped me forget the time I was punched in the stomach on the playground by another student, completely unprovoked, and then brought to the principal’s office to be spanked.

She helped me forget that my best friend in third grade was beaten nearly every day — and that Sister Antionette, the nun who beat him, held him back a grade so she could beat him again for another year.

While Nature couldn’t stop the abuse, she provided a balm where none was offered.

I’d jump off the bus, dart home, tear off the tie that hung like a noose around my neck, and run into the forested arms of my lover. With Nature, I always felt unconditional acceptance.

We would flirt with abandon. I teased her, dared her to love me as much as I loved her, dared her to love me to the very edge of self-destruction. We played the games lovers play. She always won. “But only because I let you win,” I taunted.

When the moon waxed full and flooded the salt marsh near my childhood home, I’d venture out before the tide’s crest, eager for a playful fight. I’d find my way to some thin sliver of ground, a spot slightly higher than the land around it. I’d lay claim, drive a stake into the mud and attach a rag to its top to let Nature know what king now reigned here. Then I’d await my lover’s watery wrath and the inevitable advance of the sea.

The tide would push in gradually, conquering a few inches at a time, until my kingdom was reduced to a tiny island. At the last minute, I’d heroically leap to dry ground, abandoning my claim, managing a dramatic escape from a cold, briny death.

As I ran home, I’d glance back at the wreckage of my kingdom and watch Nature submerge all but my rag in her ocean’s cold, healing waters. “See,” I’d shout. “I let you win again.”

Our games were particularly fun in winter, when ice flows provided even greater opportunity for juvenile foolishness. I never came close to drowning, but twice filled my boots with icy water and returned home shivering, cold, and feeling very much loved.

Chapter 15: Zuni Enchantment

The next day, we enter New Mexico where the Zuni people have agreed to let us camp on the grounds of the Juvenile Detention Center. But with cold, windy weather persisting, officials insist on putting us inside the center instead.

For tent-dwellers accustomed to sleeping quarters the size of a compact car, the detention center’s twelve jail cells are prime real estate. All are claimed by the time I show up, and I settle for floor space in the common area with other late arrivals.

“This is the first time we’ve filled the place without arresting a single person,” jokes one of the Zuni officers.

Beyond the luxury of spending a night in jail, staff provide hospitality above and beyond anything we expect. This evening, they launder our clothes and serve a delicious dinner of standard American fare mercifully devoid of couscous. After dinner, we pile into prison vans. Guards drive us to the heart of Zuni Pueblo to watch traditional dancing in the plaza of the old Catholic church. We’re told that, in no uncertain terms, we’re not allowed to take photos or video. The documentary crew is particularly disappointed, but everyone complies.

Arriving at the village, I’m unprepared for the uniqueness of the experience. I feel as if I’ve been transported to a remote country in a simpler time. Zuni Pueblo is home to 11,000 people. It’s cozy and walkable, the houses small and simple. Adobe ovens sit outside most homes and many are in use as we pass. The director of the Zuni Main Street program, Wells Mahkee, explains that people are baking bread and making stews and roasts that will cook through the night.

Towering above the Pueblo is the flat-topped mountain called Dowa Yalanne, a high mesa sacred to the Zuni that outsiders are not allowed to visit. I admire it from the window of the prison van as the evening sun breaks through the clouds, illuminating the mesa’s steep escarpment. It’s a stunning sight, the mountain’s spiritual and physical power manifested in the setting sun’s brilliance. I give thanks that such places exist to nurture mind and spirit.

As we walk from the van to the church, the drumming and singing grow louder. What strikes me most is that nearly everyone is speaking Zuni! Here, on a reservation also unique for its lack of a casino, the language of daily life and commerce is the Native tongue.

At the church, we’re quietly ushered up a winding staircase. The air moves with tangible excitement as we reach the rooftop. The plaza below is packed with dancers. The moving display of color is like looking through a kaleidoscope, the bright patterns changing as dancers move around the plaza. The drumming and singing are riveting, hypnotic. The experience is a sensory overload, dizzying even, as if we’ve entered an altered state of consciousness without the assistance of the usual plants or drugs.

One mask stands out — drab, Earth-colored, disconcerting, a bit frightening even. Six or seven shirtless middle-aged and older men wear this mask. The mouth is a round hole protruding outward from the face, with unnaturally large and hollow eyes. The mask feels not quite human, not entirely right, as if its bearer had crawled out of a deep, forgotten underground cavern to taunt and unnerve other dancers.

“Mudheads,” Wells explains to me later. “That’s what we call them. They’re a physical representation of what happens when you procreate with someone from your own clan. They’re a symbolic warning against incest. They’re scary, but they’re also clowns. During intermission, Mudheads entertain the crowd, do funny antics, tell stories.”

We aren’t on the roof long before the prison guard says we have to leave. I regret not seeing the Mudheads’ halftime performance. But when your driver is a prison guard and says it’s time to return to jail, you obey.